- BY Kevin Barry BSc(Hons) MRICS

- POSTED IN Latest News

- WITH 0 COMMENTS

- PERMALINK

- STANDARD POST TYPE

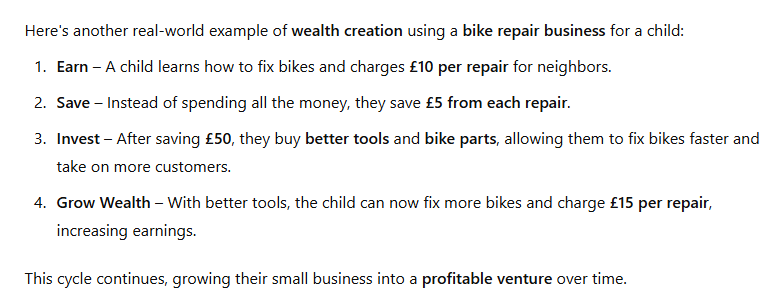

Wealth creation is based on the above simple premis. It has been lost. It has become a hand out, not a hand up mentality.

Over the past decade, the UK, including Northern Ireland, has indeed experienced a prolonged period of austerity measures, largely stemming from efforts to reduce public spending and address fiscal deficits following the 2008 financial crisis. In Northern Ireland, this has been particularly pronounced due to its unique economic and political challenges, which have hindered wealth creation. Let’s unpack why wealth generation has stalled, why Northern Ireland’s leaders claim there’s no money to invest, and whether a form of agreed or shared Ireland could offer a solution.

Why No Real Wealth Creation in Northern Ireland?

- Austerity’s Lasting Impact:

Austerity in the UK, ramped up after 2010 under the Conservative-led government, aimed to shrink budget deficits through cuts to public spending. In Northern Ireland, this translated into reduced funding via the Block Grant from Westminster, which constitutes the bulk of its budget. Public sector employment—a significant economic driver in the region—faced wage freezes and job losses, dampening local demand. Private sector growth, meanwhile, has been sluggish, partly because austerity stifled infrastructure investment and innovation funding, key ingredients for wealth creation. - Structural Economic Weaknesses:

Northern Ireland’s economy has long been over-reliant on the public sector and low-productivity industries. Unlike the Republic of Ireland, which leveraged low corporate taxes (12.5%) and EU membership to attract multinational firms—fueling the “Celtic Tiger” boom—Northern Ireland lacks a similar strategy. Its industrial base, once robust with shipbuilding and manufacturing, has declined, and replacement sectors like tech or high-value services haven’t scaled sufficiently. The region’s GDP per capita lags behind both the UK average and the Republic, reflecting a persistent productivity gap. - Political Instability:

The stop-start nature of devolved government, including a three-year collapse of the Northern Ireland Assembly (2017–2020), has paralyzed decision-making. Major projects—like improving transport links or boosting skills—require consistent policy, which has been absent. Investors crave stability, and Northern Ireland’s political fractiousness, compounded by Brexit uncertainties, has deterred private capital. Ministers’ claims of “no money” often reflect this deadlock: even when funds exist, agreement on how to spend them is elusive. - Brexit Complications:

Since the UK’s exit from the EU, Northern Ireland’s position has been awkward. The Northern Ireland Protocol (now Windsor Framework) keeps it aligned with some EU rules to avoid a hard border with the Republic, but this has disrupted trade with Great Britain, its biggest market. Businesses face extra costs and red tape, undermining competitiveness. Meanwhile, the Republic benefits from full EU access, widening the economic divergence across the island.

Why Ministers Say There’s No Money to Invest?

Northern Ireland’s budget is heavily dependent on the Block Grant, which has shrunk in real terms due to austerity and inflation. Unlike the Republic, it can’t borrow significantly or set its own tax rates (beyond minor tweaks), leaving it at Westminster’s mercy. Local revenue from rates and fees is limited, and the private sector’s weakness means tax receipts are low. Ministers aren’t entirely wrong—discretionary funds for bold investments are scarce—but this also reflects a failure to prioritize or lobby effectively for more resources. The UK government’s “Levelling Up” agenda has brought some cash, but it’s often piecemeal, not transformative.

What Next Without Political Reform?

Without political will to overhaul this system, Northern Ireland risks stagnation. The current power-sharing model, while vital for peace, often prioritizes sectarian balance over economic ambition. Reforming it to focus on wealth creation—say, by streamlining decision-making or aligning policies with growth sectors—requires consensus that’s hard to achieve. Absent reform, the region could remain a low-growth outlier, dependent on subsidies from London, with living standards falling further behind the Republic’s.

The Republic’s success offers a blueprint: low corporate taxes, foreign direct investment (FDI), and export-led growth. Northern Ireland could push for greater fiscal devolution from the UK to mimic this—perhaps lowering corporation tax (currently 19%, set to rise to 25% for big firms) or creating special economic zones. But this needs political courage and UK approval, both in short supply.

Could a Shared Ireland Help?

A “shared Ireland” could mean many things: economic cooperation, a customs union, or even reunification. Each has potential to address Northern Ireland’s woes, but none is a silver bullet.

- Economic Cooperation:

Closer ties with the Republic—e.g., joint infrastructure projects or an all-island investment strategy—could leverage the South’s FDI prowess. The Republic’s tech hubs (Dublin, Cork) could spill benefits northward, but this requires unionist buy-in, which is politically fraught given identity concerns. - All-Island Economy:

A formal shared economic framework, like harmonized taxes or trade policies, could boost efficiency and attract firms seeking seamless access to both UK and EU markets. The Republic’s wealth (GDP per capita now far exceeds the UK’s) could fund investment, but Northern Ireland’s subsidy from the UK (around £10 billion annually) would need replacing—a massive hurdle for Dublin taxpayers. - Reunification:

Full integration into the Republic, as envisioned by some nationalists, might align Northern Ireland with a dynamic, EU-integrated economy. Studies suggest short-term costs (e.g., absorbing public sector pensions) but long-term gains if productivity rises. Yet, this assumes unionist acquiescence, which Brexit and demographic shifts (a growing Catholic population) haven’t yet secured. The Good Friday Agreement mandates consent via a border poll, and polls show support hovering around 30–40%—not yet a majority.

Realism Check

A shared Ireland, in any form, hinges on political will north and south. The Republic’s government has mused about unity but balks at the cost. Northern Ireland’s unionists resist anything smacking of Dublin’s influence, fearing cultural erosion. Without a crisis or bold leadership, incremental steps—like enhanced North-South trade under the existing framework—are more likely than radical change. Meanwhile, the UK’s economic grip limits Northern Ireland’s options unless Westminster devolves more power.

In short, Northern Ireland’s wealth creation lag stems from austerity, structural flaws, and political inertia. A shared Ireland could help, especially economically, but only if the political stars align. For now, pushing for fiscal autonomy within the UK might be the most pragmatic step—though even that demands a resolve that’s been absent.