- BY Kevin Barry BSc(Hons) MRICS

- POSTED IN Latest News

- WITH 0 COMMENTS

- PERMALINK

- STANDARD POST TYPE

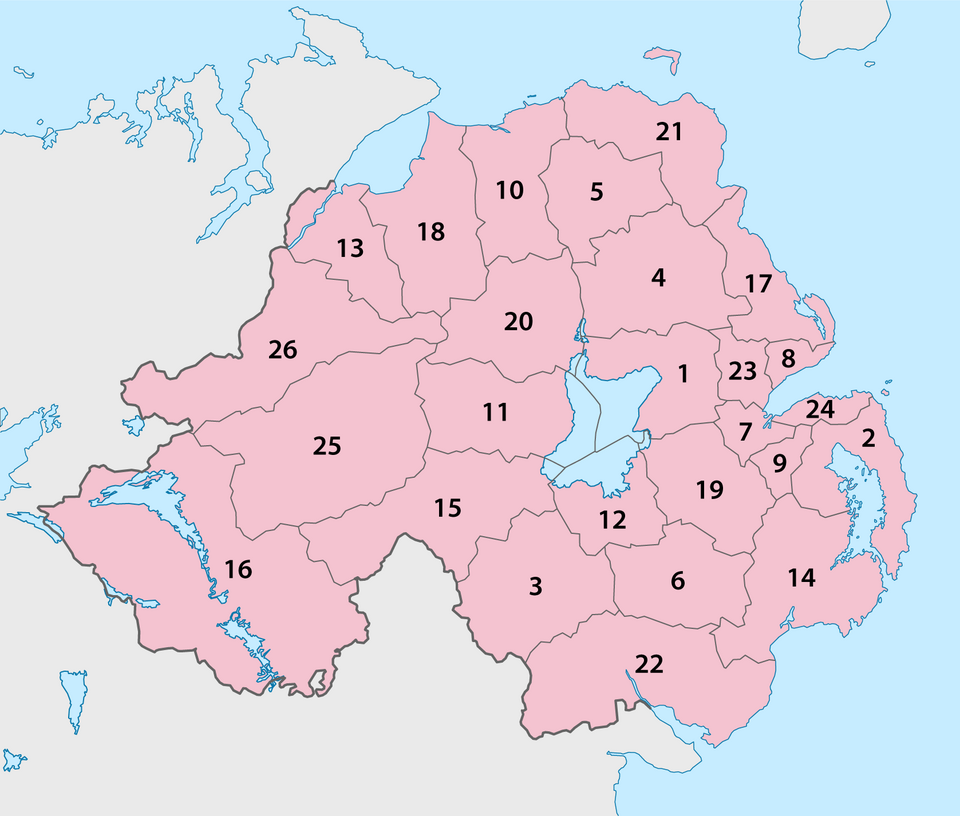

The transition from 26 councils to 11 “super councils” in Northern Ireland, implemented in April 2015 as part of the Review of Public Administration (RPA), was a significant restructuring of local government aimed at improving efficiency, reducing costs, and enhancing local decision-making. Below is an analysis of this shift and an evaluation of whether its intended aims have been realized, based on available evidence and developments over the past decade.

Background and Aims

The RPA, initiated in 2002, sought to reform public administration in Northern Ireland, including local government. By 2012, the Northern Ireland Executive settled on reducing the 26 district councils—established in 1973—to 11 larger “super councils.” The key aims were:

- Cost Savings: Projections estimated savings of £438 million to £570 million over 25 years through economies of scale and reduced administrative overheads.

- Increased Efficiency: Larger councils were expected to streamline operations and eliminate duplication in service delivery.

- Enhanced Local Power: New responsibilities, such as planning, local economic development, and community planning, were devolved to councils to empower local communities and improve service responsiveness.

- Modernization: The reform aimed to update a system seen as fragmented and overly dependent on central government, aligning it with contemporary governance needs.

Analysis: 11 Super Councils vs. 26 Councils

Structure and Scale

- 26 Councils (1973–2015): These smaller districts had an average population of about 65,000 and were responsible for limited functions like waste collection, leisure services, and local amenities. Major services (e.g., education, housing, roads) were centralized under Stormont or other agencies due to historical concerns about local discrimination during the Troubles.

- 11 Super Councils (2015–present): The new councils serve larger populations (ranging from 116,800 in Fermanagh and Omagh to 345,400 in Belfast, per the 2021 census) and cover broader geographic areas. They assumed additional powers, notably planning, which shifted from Stormont’s Department of the Environment to local control, alongside roles in economic development and community planning.

Financial Performance

- Cost Savings: The promise of significant savings has not fully materialized. The total net cost of running the 26 councils in their final year (2014/15) was £742.3 million, while the 11 councils cost £791 million in 2018/19—an increase of nearly £49 million. By 2021/22, spending had risen by 7.8% compared to 2012/13, with councils dipping into reserves or borrowing to cover an average annual shortfall of £32.57 million. The Northern Ireland Audit Office reported a £128 million gap between income and expenditure in 2024, the largest since the reform.

- Efficiency Savings: Councils reported £21.49 million in efficiency savings, but these have been offset by rising costs, including staffing (an increase from 9,790 to 10,136 full-time equivalent employees between 2014/15 and 2018/19) and new responsibilities without adequate funding. The Department for Communities (DfC) noted in a recent report that it’s “too early” to judge cost-effectiveness, citing political instability and a limited timeframe for leveraging benefits.

- Comparison: The 26-council system, while fragmented, operated within a smaller budget, partly because it had fewer responsibilities. The 11-council model’s increased scope has driven costs up, challenging the economies-of-scale argument.

Service Delivery and Efficiency

- Planning: A flagship new power, planning has seen mixed results. In 2023/24, the average processing time for local applications was 20.8 weeks, exceeding Stormont’s 15-week target and up from 19 weeks the previous year. Only three councils met the target, and a 2022 Northern Ireland Audit Office report criticized the system as inefficient, failing to deliver for communities or the economy. However, councils argue it’s more responsive to local priorities than the centralized system under the 26 councils.

- Community Planning: This new function has fostered collaboration between councils, government, and communities, offering a framework to address local needs holistically—something the 26 councils lacked. Yet, tangible outcomes remain hard to measure a decade on.

- Comparison: The 26 councils were limited in scope, often passing responsibilities to Stormont, which reduced local accountability but kept operations simpler. The 11 councils have broader remits but struggle with capacity and funding, leading to delays and inefficiencies in key areas like planning.

Local Empowerment and Governance

- Devolution of Powers: The transfer of planning, economic development, and off-street parking has given the 11 councils more influence over local destinies than their predecessors. Initiatives like City and Growth Deals (e.g., Belfast Region City Deal) highlight their potential to drive economic progress, a role the 26 councils rarely played.

- Democratic Representation: The reduction from 582 to 462 councillors has raised concerns about diminished local representation. Ten of the 11 councils are now dominated by either unionist or nationalist blocs, potentially sidelining minorities, though statutory protections exist under the Local Government Act. Belfast remains a hung council, with Alliance holding the balance.

- Comparison: The 26 councils offered finer-grained representation but lacked the authority to shape policy significantly. The 11 councils have more power but cover larger, more diverse areas, sometimes diluting local voices.

Were the Aims Realized?

- Cost Savings: Largely unrealized. Spending has increased, and projected savings remain elusive, undermined by transitional costs, insufficient central funding, and economic pressures like inflation and austerity.

- Increased Efficiency: Partially achieved. Some administrative duplication was eliminated, but service delivery (e.g., planning) lags, and staffing levels have risen rather than fallen.

- Enhanced Local Power: Achieved to an extent. The devolution of powers has strengthened local decision-making, enabling initiatives like growth deals, though further devolution (e.g., regeneration powers) stalled after “phase one.”

- Modernization: Achieved structurally. The system is more aligned with modern governance needs, but operational challenges and political instability have hampered its effectiveness.

Conclusion

The shift to 11 super councils from 26 has delivered a mixed outcome. It has modernized local government and granted councils greater autonomy, fulfilling part of the RPA’s vision. However, the core aims of cost savings and efficiency have not been fully realized, with rising expenditures and service delays casting doubt on the “super” label. Compared to the 26-council system, the 11 councils offer more potential for local impact but face significant financial and operational hurdles. Political instability at Stormont and incomplete devolution have further limited progress, suggesting that while the reform was a shake-up, its promise as a transformative success remains, for now, a let-down in key areas. A longer timeframe and more robust support from central government may yet reveal its full impact.